When, in May 2025, the UK Met Office reported that “Northwest European waters are currently experiencing an extreme marine heatwave“, the yachting community in Plymouth had been talking about worsening fouling on their boats for weeks.

It seems that lately, slime and algae on hulls appear earlier in the season and seawater intakes are colonised more aggressively than, say, 30 years ago.

What may be solved on a small pleasure craft with a scrubber or one of those flexible spiral drain pipe cleaners, is much more problematic on the more complex systems of bigger ships.

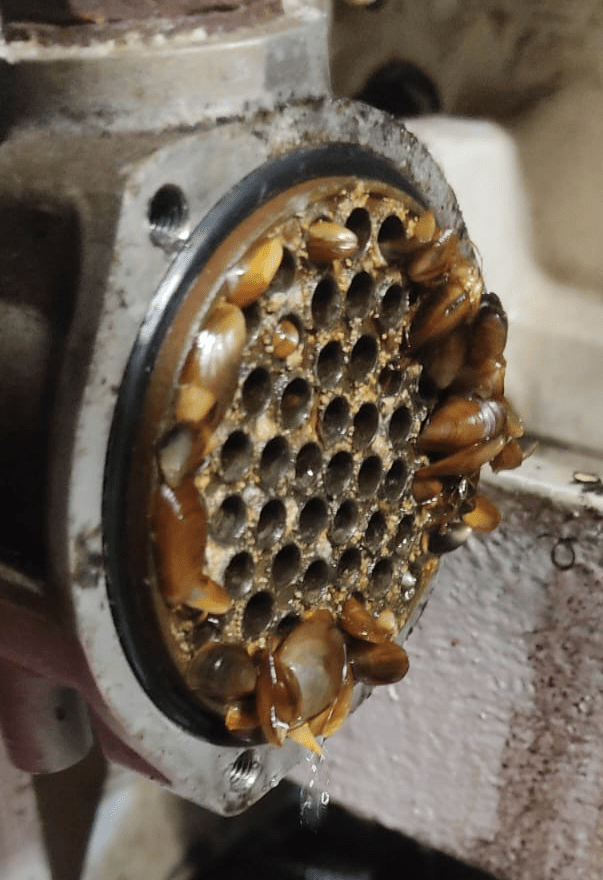

Take the sail training tall ship Pelican of London as an example: the contents of variously sized strainers and heat exchanger systems illustrate that the natural process of biofouling, commonly visible on exposed submersed surfaces, also occurs deep within the machinery we take to sea.

It all starts with micro-fouling, which is the formation of a biofilm by bacteria and other microorganisms on any submersed surface, whether it’s a ship wreck or ship’s hull, a rock or harbour structure, an engine cooling pipe or even another organism. This biofilm is an ideal substrate for macro-fouling organism, such as seaweed, barnacles, seasquirts and mussels. These larger organisms may enter the system tiny larvae, settling within and growing.

Biofouling on hulls causes drag and increases fuel consumption, leading to higher cost and greenhouse gas emissions. It also facilitates the transfer of organisms between different ecosystems. Internal biofouling can impair the cooling water flow and the efficiency of the heat exchanger, potentially causing engine damage through overheating and increased maintenance cost. Chris Cavaliere, technical manager of Pelican, states: ‘since departing Barrow in Furness at the end of the winter maintenance period, the engineers are having a constant battle trying to stay ahead of biofouling within the sea water intakes and piping. The marine growth clogged heat exchangers and pipework and damaged pump impellers, causing increased temperatures when running the main engine and generators.’

My question here is: do marine heatwaves and more generally, warming seas, increase the biofouling problem for the marine industries?

The short answer is Yes!

As any undergraduate biology student working on laboratory cultures can tell you, the development and growth rate of bacteria, insects, mollusks, algae – i.e. organisms in categories that cause biofouling – are affected by temperature, in a positive way (up to a point).

In the marine context this anecdotal/common sense statement is backed up by scientific research. For example, Khosravi et al. (2019) showed that seawater warming of 2°C led to a significant increase in fouling coverage and changes in community structure and diversity. Their conclusion was clear: warmer seas increase biofouling pressure. A lot of research has been devoted to the commercial growing of mussels around the world, with key studies agreeing on the fact that higher temperatures (within the physiological range of the species of interest) expedite the development of planktonic larvae from fertilised eggs (e.g. Nair and Appukuttan, 2003). The settlement of larvae on hard substrate occurs at between 9 and 24 days, depending on the species (Ompi and Svane, 2018) and again, the temperature.

Perhaps there is some good news in the latter statement: the settlement and survival of larvae has an upper temperature limit (Nair and Appukuttan, 2003) and therefore, there will be limits to fouling by shellfish deep inside the heat exchanger system if temperatures exceed the tolerable threshold for the most damaging ‘pesky critters’.

The battle against biofouling has led to the development of a wide range of chemical, physical and technical solutions, each with its own set of applications, advantages and disadvantages. Unfortunately, a lot of them are toxic to marine life, as the extreme harm to coastal ecosystem by the most effective ever antifouling compound for hulls, tributyltin, has illustrated.

Whether metals or synthetic compounds used in coatings on hulls, their antifouling properties rely on their toxicity to marine life (e.g. Antizar-Ladislao, 2008; Intissar et al., 2021) and increasingly, legislative control curtails the use of biocides for antifouling coatings (e.g. Pantaenius). Perhaps a more sustainable future lies in the optimisation of physical fouling prevention and the employment of biomimicry and nanotechnology (e.g. Satasiya et al., 2525; Tian et al. ,2021). Among the former, ultrasonic systems (e.g. Practical Boat Owner, Pantaenius, Evac, Yachting Monthly, Huang et al., 2024) appear to be advanced and promising solutions for ships and yachts with continuous electricity supply.

Meanwhile, the engineering team of Pelican of London have developed and implemented new maintenance plans for protecting their internal systems from biofouling. But, as Chris Cavaliere put it: ‘maintenance alone cannot resolve these issues and I have sought further input from scientists and specialist teams, including the marine company Cathelco®, who intend to install teir Marine Growth Prevention System (MGPS) onboard’. The MGPS is based on electrolytic dosing of metals into the cooling water from copper and aluminium electrodes. For Pelican of London Ltd, this state-of-the-art solution, which has been already fitted to some 50,000 commercial ships, will make an important contribution to future-proofing and, along with planned maintenance, improving the reliability of the vessel.

One thing seems certain: the biofouling problem will grow with warming seas for all marine industries, whether related to infrastructure, power or water supply, shipping or recreation. Let’s hope that R&D efforts will soon come up with workable solutions for all sectors.

References

Antizar-Ladislao B. 2008. Environmental levels, toxicity and human exposure to tributyltin (TBT)-contaminated marine environment. A review. Environment international 34(2) 292-308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2007.09.005

Huang X et al. 2024. Application of ultrasonic cavitation in ship and marine engineering. Journal of Marine Scence and Application 23, 23-38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11804-024-00393-7

Intissar A et al. 2021. Antifouling processes and toxicity effects of antifouling paints on marine environment. A revew. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 57, 115-130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2017.12.001

Khosravi M et al. 2019. Impact of warming on biofouling communities in the northern Persian Gulf. Journal of Thermal Biology 85, 102403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2019.102403

Nair RM and Appukuttan KK. 2003. Effect of temperature on the development, growth, survival and settlement of green mussel Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758). Aquaculture Research. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2109.2003.00906.x

Ompi M and Svane I. 2018. Comparing spawning, larval development, and recruitments of four mussel species (Bivalvia: Mytilidae) from South Australia. Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation, 11(3), 576-588. https://bioflux.com.ro/docs/2018.576-588.pdf

Satasiya G, Kumar MA, Ray S. 2025. Biofouling dynamics and antifouling innovations: Transitioning from traditional biocides to nanotechnological interventions. Environmental Research 269, 120943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2025.120943

Tian L et al. 2021. Antifouling technology trends in marine environmnental protection. Journal of Bionic engineering 18, 239-263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42235-021-0017-z

Pingback: Embracing the Challenge | Challenging Habitat